As a Science teacher I am well-acquainted with the idea of students working as partners in a lab setting. It’s a time-honored practice based on a variety of rationales, depending on the setting. Lab partners, or indeed partners in any academic setting, might be placed together for logistical reasons: there may be multiple responsibilities that need to be shared, there may be limited equipment, limited lab supplies, limited computers, or limited space. There may be pedagogical reasons as well: students can assist each other in learning material, or learning to work together may even be the goal of the lesson.

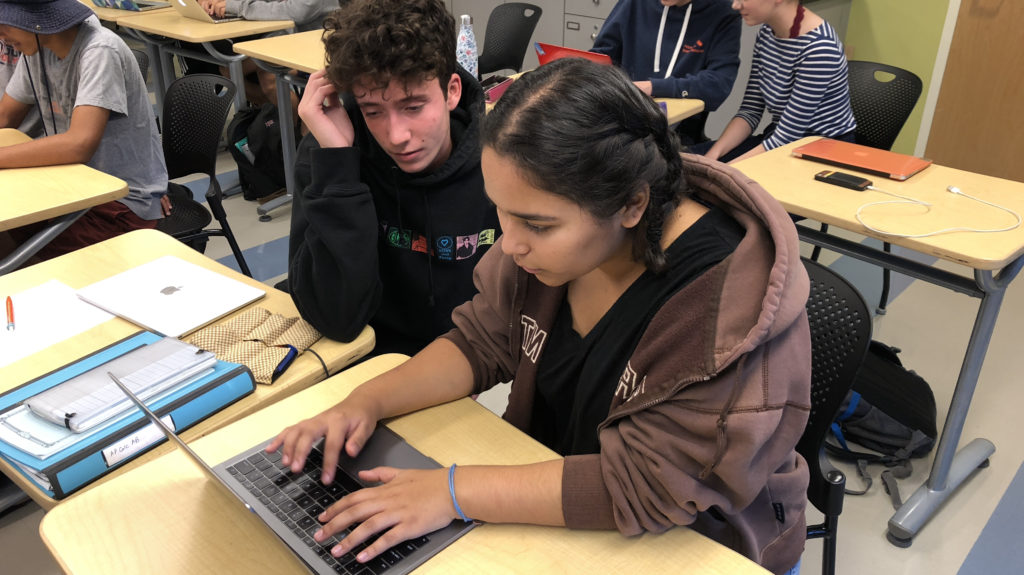

In computer programming classes, “pair programming” may be used, with one student typically “driving” (entering code on the computer), and another “navigating” (dictating code, catching typos, etc.) There are variations on the specific responsibilities of each role, but the general idea is that two heads are better than one, and that an ongoing conversation as the code is developed will produce a stronger product. Pair Programming isn’t just for classes–it’s actually used in the software industry by some organizations.

Regardless of the context, there are bound to be challenges when two people are asked to work together in a demanding situation. One common challenge is when two students have varying abilities or levels of success. Sometimes teachers will even pair students with this in mind, either placing students of similar level with each other, or pairing a successful student with a challenged student with the hope of fostering some impromptu peer tutoring. (I’d suggest that there are issues with both of these strategies, but we’ll leave that for another time.)

In my courses I’ve developed a Pairing Strategy that seems to be working well for my students based on the success I’ve seen in their assignments and their behaviors in the classroom. It works like this:

1. Introduce the idea of Paired Work.

Discuss the benefits and talk about the challenges. Mention the fact that there may be different roles to be played, and that those roles will likely change over the course of the experience.

2. Discuss behavior.

Point out that people need to be on their best behavior when working as a pair. Respect is an important part of this process, and that includes during that first moment when you learn who you’re going to be working with. A loud cry of “Oh, man, I got stuck with Christine??!” doesn’t get you off to a great start, and celebrating that you got paired with the person with the highest test average isn’t appropriate either.

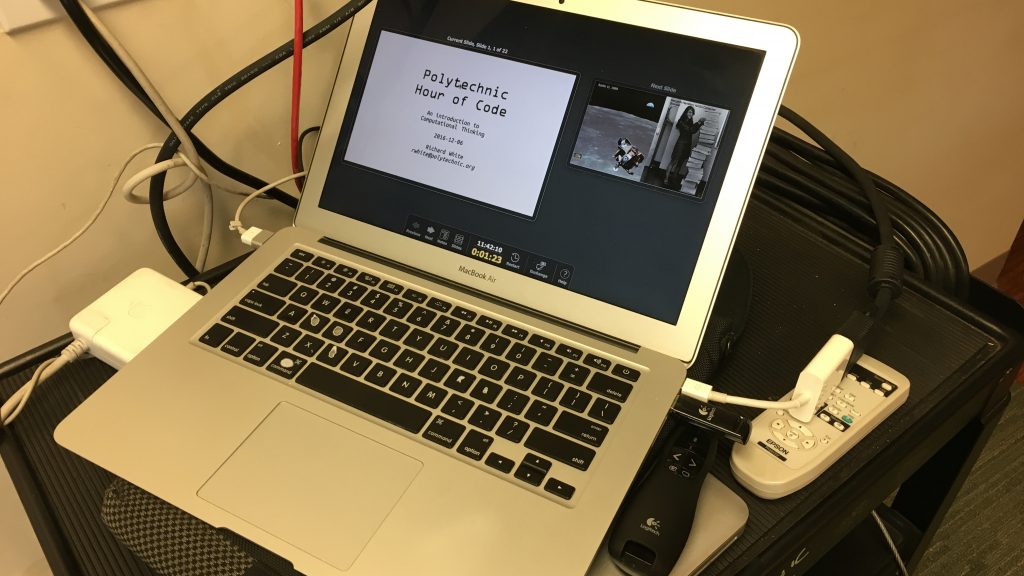

Code.org’s video on Pair Programming, while a bit cheesy and clearly intended for a more Middle School audience, pretty much nails it.

3. Explain the Pairing process.

Very often I’ll use this computer program to pair students randomly. They’ve come to appreciate the excitement of finding out who they’re going to be working with.

In the case of Pair Programming, I’ll be very specific. Just before running the program so that students can see the results on the overhead projector, I’ll say that the partner listed on the left side of list will be the first “driver,” and that students will be using that person’s computer for the project. The person listed on the right side of the list will be the navigator, and will get up and move over to where the driver is sitting to get started.

#!/usr/bin/env python3

"""

random_partners.py

This program takes a list of students in the class and assigns them randomly

to a series of groups of a specified size.

@author Richard White

@version 2018-10-10

"""

import random,os

def main():

all_students = ["Kareem","Lucas","Marcela","Dylan","Gwen","Ella","Adam","Carrie","Patty","Annie","Audrey","Aidin","Sinjin","Henry","Robby","Sean","Ms. Dunham"]

students_present = ["Kareem","Lucas","Marcela","Dylan","Gwen","Ella","Adam","Carrie","Patty","Annie","Audrey","Aidin","Sinjin","Henry","Robby","Sean","Ms. Dunham"]

os.system("clear")

groupsize = eval(input("Enter # of people in a group: "))

os.system("clear")

i = 0

print("PARTNERS:")

while len(students_present) > 0:

if i > 0 and i % groupsize != 0: # Print commas after first one in group,

print(", ", end='') # but not if done with group

random_student = random.choice(students_present) # Pick random student

print(random_student,end='')

students_present.remove(random_student) # Remove name from list

i += 1

if i % groupsize == 0:

print() # Space down at end of members

print()

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

4. Run the program

Here’s a sample run from running this program in my Introductory Computer Science course:

PARTNERS:

Robby, Adam

Kareem, Aidin

Ella, Annie

Henry, Patty

Gwen, Ms. Dunham

Lucas, Carrie

Dylan, Audrey

Sean, Sinjin

Marcela

5. At an opportune time, have students exchange roles.

During every assignment, assuming I’ve done a good job of building in an unexpected challenge or new idea, I’ll ask for attention: “Hands off the keyboard!” or something similar. I’ll pose a question regarding the work that they’ve done, or share some observations I’ve made, or ask if anyone has come across the difficulty that I’ll expect they’re going to have. After this brief interruption, I’ll ask them to change roles and continue their work.

Sometimes the process doesn’t work quite right the first time, or there may be mid-course corrections required if students get a little sloppy in their treatment of each other. That can happen in any classroom environment. The fact that students are truly randomly assigned, however, seems to keep them on their best behavior. They know that I don’t have any intentions in assigning them to a given partner–this is just who they’re going to be working with today.

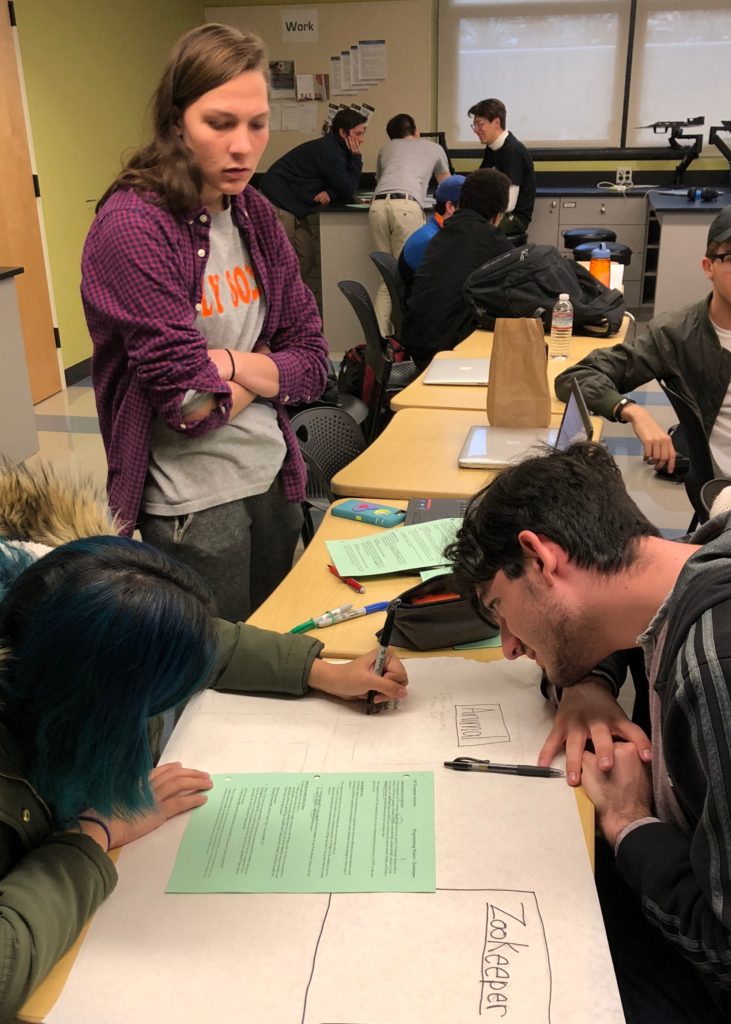

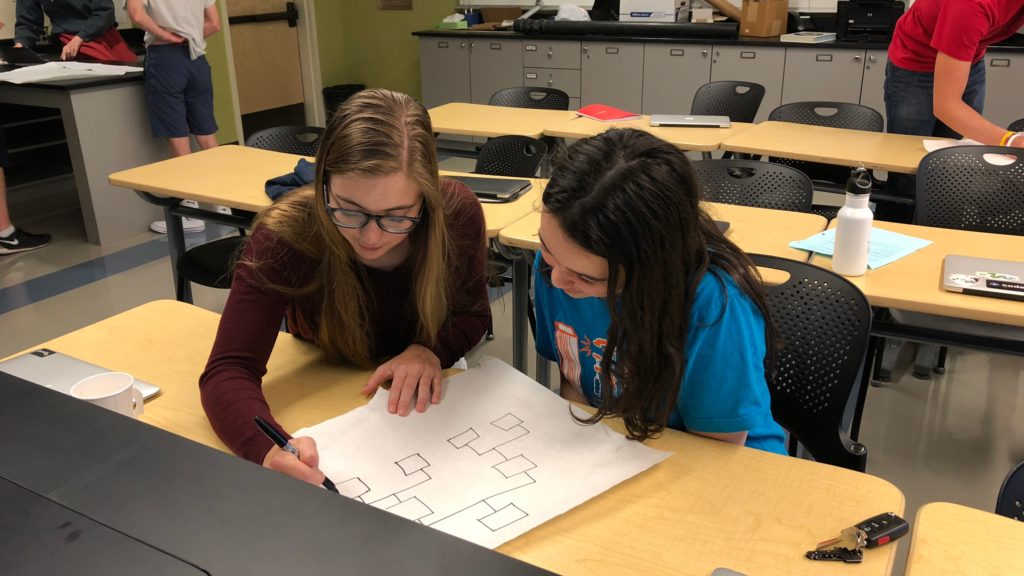

Here’s a video clip of my students working on a programming assignment in a Paired environment.

Overall, I’ve been very pleased with how this process has worked with my students over time. Give it a try in your classroom and see what you think!