THE REAL DEAL: A different kind of hybrid

2010-12-30

by Richard White

This site has been devoted to discussing the hybrid classroom, in which a traditional classroom-based curriculum has online components as an integral part of the course. For three weeks in November, however, my science students participated in a different kind of hybrid experience.

Science courses, and in particular Advanced Placement science courses, are a tricky animal. On the one hand, we’ve got people’s natural curiosity regarding the world about them, and an innate desire to play with stuff and figure things out–these qualities appear to be hardwired into us, evolutionarily. People love science, or at least the idea of science: from Discovery Channel’s “Shark Week”, to explosions on Mythbusters, to dropping a few Mentos into a bottle of Diet Coke, most people find this stuff interesting on at least some level.

On the other hand, you’ve got your typical science course. It takes place in a classroom, and there are notes to be taken, facts to learn, and tests that demand no small amount of regurgitation, all at a breakneck pace that leaves little time for reflection or a deeper consideration of things. Once a week or so there’s a lab, in which the students typically follow a set of instructions–more or less successfully, it is hoped–and subsequent write a short report summarizing the experience. It’s kind of cool getting to play with the equipment, but… does it really count as science? Where’s the investigation, and the thrill of discovery? Where’s the fun?

The sad truth is that it’s extraordinarily difficult to come up with good laboratory experiences that are meaningful, relevant, appropriate, fun, and safe. My friend Karen Wilson, a chemistry teacher, had the misfortune to have a student in her class who chose to “leave the path” during an independent project, and literally blew off his hand. She spent several years of her professional career defending herself in the subsequent lawsuit: ‘Yes,’ she’d demonstrated proper safety procedures; ‘no,’ she hadn’t authorized the experiment that led to the loss of his limb. The suit against her ultimately failed, but not before it had taken its toll on her.

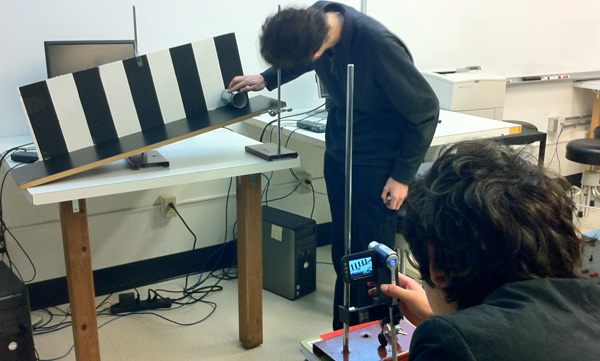

Against all odds, then, my AP Physics students are having a little fun in lab right now. Their assignment for this most recent unit is to a) theoretically develop the equations for the rolling motion of a hoop, disk, and sphere; b) develop an experimental procedure and collect data regarding the real world motion of these objects, and c) analyze and reconcile the experimental results with what is predicted by theory. Okay, that might not sound that interesting to you, but for them, it’s a surprising breath of fresh air.

Why? Why are they more interested in this lab?

- They have 3 weeks to work on this lab.

Even if it’s going to be a little more work in the long run, they’re appreciating the fact that they get to focus on one thing for a little while. - They have an open-ended problem to figure out.

Granted, it’s not THAT open-ended–they are clear specifications for what’s expected. But the path they’re going to take to get there, from what data they want to collect to how, specifically, they’re going to go about collecting that data, is completely up to them. Seriously, when I was introducing the lab, they could barely wait for me to shut up so that they could start brainstorming, planning, drawing sketches, and assembling preliminary set-ups to test how feasible they’re data collection strategies might be. It was amazing. - This is a high-stakes assignment.

In line with the requirement that they’ll be submitting a very formal write-up on this one–a word-processed document, with equations, data tables, and graphs all electronically created–there’s more on the line: this assignment is worth the equivalent of a full test, and points like that are hard to come by in my class. For those students who need just a little more incentive to do a good job–in addition to the inherent appeal–there’s the promise of points.

This kind of “authentic assessment” or “performance-based learning” is not entirely new of course–not if you’ve been in the game long enough to recognize those expressions, which received some buzz when they were proffered years ago. And this strategy for fostering learning isn’t a silver bullet for highest-risk students who find themselves completely disenchanted with anything associated with school or education.

But for teachers and students who are looking for something a little different, this is a great way to add some real world legitimacy to your curriculum, AND have a little fun in the process.

What Real World experiences are you able to build into your teaching?