Whither Data?: Dude, where’d my content go?

by Richard White

2014-09-20

Part II in our series.

In a previous post, Whither Media?, we explored the ongoing transition away from physical media, and what implications this transition might have. The related question is Whither Data?: What happens when your content—your written documents, photos, email, music, etc.—are all stored on somebody else’s computer?

The Cloud is a term that has a number of definitions, but typically it refers to a collection of servers run by a company that (usually) offers a user access via Internet to that data and those services. In addition to offering Internet access, a cloud-based service typically implies multiple servers hosting redundant copies of the data, providing faster access to the user and backups of a user’s data.

If you use Google’s Gmail, your email is stored on their servers, “in the cloud.” If you use Google Docs, your documents are stored on servers, “in the cloud.” Microsoft’s Office 365 stores your Word, Excel, and PowerPoint documents “in the cloud.” And although you may not think of it this way, many social networking sites such as Facebook also provide content and services “in the cloud” so that your conversations, photos, status announcement, comments, and Likes are store where you and others can view them.

There are a number of powerful advantages to using cloud-based services, and most of these are self-evident, especially to teachers. At my school, which provides Google Apps for Education (GAFE) to teachers and students, we’ve been able to offload our email services to Gmail and provide Google Docs and Calendars to the entire community, allowing for teaching strategies and communication workflows that simply weren’t possible before. Content Management Systems (CMS) and their educational offspring Learning Management Systems (LMS) provide a structure—usually a proprietary one—in which a teachers information can be delivered and a students interactions with that information can be tracked.

I love the fact that the ability to share data from user to user and machine to machine has become easier. Without cloud services, teachers would be forced to a) try manage an endless and non-linear flow of emailed attachments (something some of us still do, I’m sorry to say), or b) implement and manage our own servers to which students can upload documents, and from which they can download them. (Actually, I do do this, but it’s in the context of a computer science course in which those processes are part of the curriculum). Cloud services allow for shared files, shared folders, and drag-and-drop functionality that “just works” (most of the time).

There are two caveats here, however. The first concern is security. Unless students are encrypting their documents before uploading them, there’s the possibility that the information in those documents—perhaps confidential, private information—may be visible to others, either in transit or on those servers. The reality for most teachers, I think, is that the documents that students are sharing with us—book reports, essays, lab reports, homework assignments—don’t require a high degree of security, and so maybe this is just fine. If you were having students email Word documents to you before, having them work on a GoogleDoc on Google’s servers is at least as secure, and almost certainly more unless they’ve elected to make the document’s contents available publicly.

I am not a doctor or lawyer and am not aware of the specific legal requirements concerning the secure storage of patient or client information, but I would investigate that carefully before using cloud services for these purposes.

Perhaps a more significant concern for teachers and students, however, is retaining access to cloud-based content over the long term. Low-priority content like quizzes or in-class essays may not be of much concern to students, but more significant essays, research papers, or portfolio work has a higher value, and may even be submitted to colleges as part of an application. Ideally, a student would be able to retain access to their work—and it is their work, isn’t it?!—for some indeterminate time into the future. Which cloud-based services allow for that?

The notorious offenders here are the providers of online books—where online notes and marginalia disappear when your one-year access license expires—and the various Content Management and Learning Management Systems, with password-protected access that may not extend beyond the current year. Students who create or store documents in these systems are at high risk of losing access to them when the end of the school year comes around, or the next school year starts begins (depending, of course, on the administration of the system).

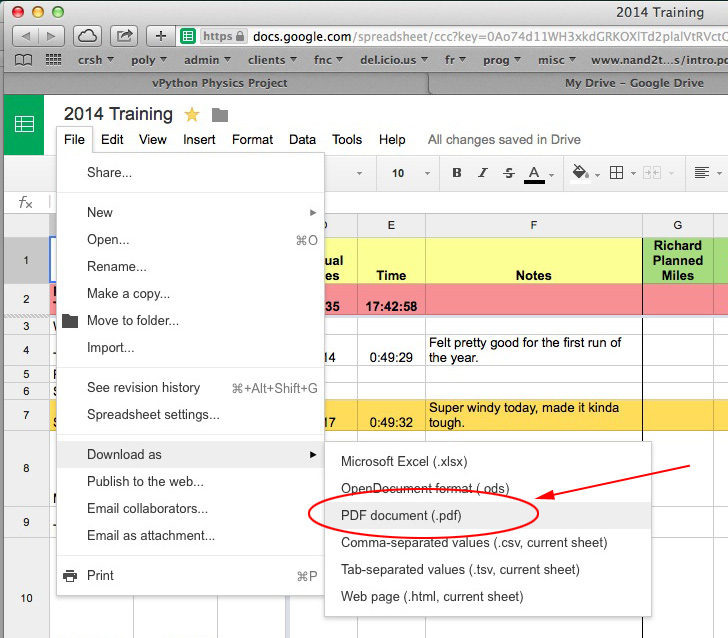

The same may happen with Google Apps For Education, although it is much easier to export this data onto a student’s own computer or data storage device, assuming he or she has access to something more than a Chromebook. Here, a personal Google account may come in handy, although questions about privacy of these documents may be relevant.

I don’t think we’ve yet reached the point where lost access to data is a broad concern, although some are wrestling with this issue already (as mentioned previously here. 34:20 in show). As we ask that are students create more and more of their work in a digital form, however, it’s fair that we keep these questions in mind: ‘Should students have access to the data that they’re submitting to me?’ and ‘How do I go about facilitating that access?’