HOW TO FLIP YOUR CLASSROOM

2012-06-30

by Richard White

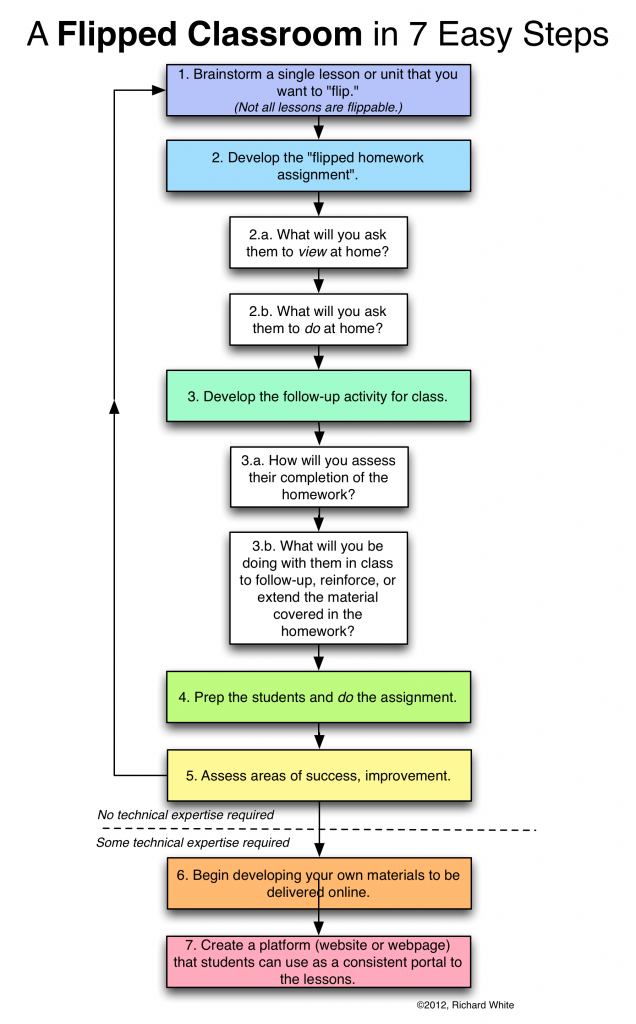

Flipping a classroom consists of off-loading (usually to the Internet) some of the non-interactive aspects of one’s classroom, in favor of using time in-class for activities that take advantage of the teacher’s immediate presence.

Perhaps the most obvious example might be this:

|

At school |

At home |

| Standard classroom |

Student listens to teacher introduce new math topic |

Student goes home and tries to do homework, often unsuccessfully and without the opportunity to get questions answered in a timely manner. |

|

At home |

At school |

| Flipped classroom |

Student watches brief video explanation of new topic online, or reads new material to be discussed in class the next day. |

Student works on “homework” problems, with teacher answering questions or providing clarifying follow-up as necessary. |

Pretty straightforward, right? It’s a good idea, and there’s lots to recommend it. In fact, you may already be implementing some aspects of the flipped model, even if nobody has ever referred to it by that name before. Some teachers give students time in class to read a chapter in novel, and then discuss it in the remaining class time. Others choose to assign the reading as homework, leaving more time in class for re-reading passages, interpreting what the author has written, or general discussion.

If you’ve done something like this, congratulations—you’re officially part of the most recent trend in education, and you should feel free to strut around saying things like, “‘Inverted learning?’ Honey, I’ve been flipping my class for years…”

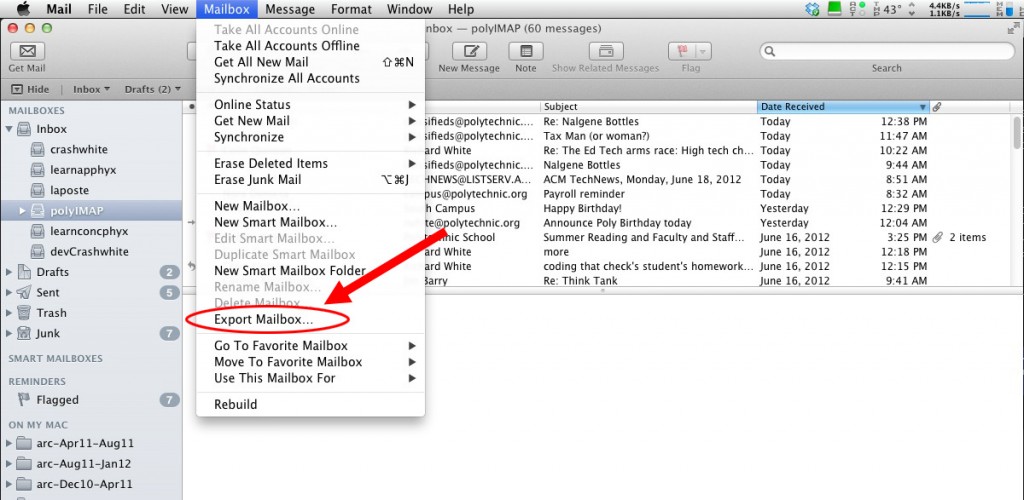

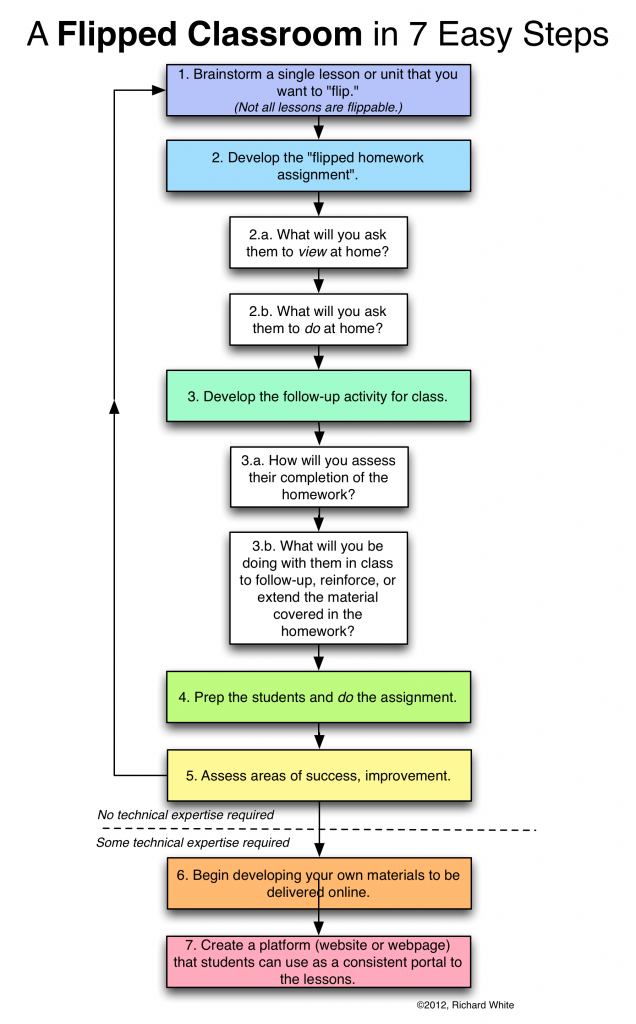

If you haven’t tried this yet, or you’re just looking for a few ideas on how to get started trying this out, let’s take a look at the stops involved in doing such a thing. And then read below for some specific bits of advice regarding the process of converting to a flipped classroom.

Things to think about:

Start with a single day, or a single week, or a single unit.

You don’t need to reorganize your entire semester to begin trying out a flipped model. A day or two will give you a chance to see what the benefits and challenges are, and give you some good ideas on how to go about designing a flipped model on a larger scale.

Be patient with the students.

It may take them a little time to adjust to this at first. Under the traditional model, it’s easy for a teacher to ascertain whether a student has turned in a homework assignment, and easy for students to recognize something tangible like the piece of paper with their writing on it. A flipped instruction model is going to ask them do something rather than make something—watch a video, read this section, interview their parents about something—and this is a little different from what they ordinarily do for homework.

What can you flip in your class?

We all teach different subjects, in different ways, so it’s a uniquely personal challenge, figuring out what you can try flipping in your own class.

Here are some ideas to get you started, following the same format listed above.

The French Revolution

|

At school |

At home |

| Standard classroom |

Teacher lectures on the the origins of the French Revolution |

Student goes home and does a worksheet or write answers to problems from a textbook. |

|

At home |

At school |

| Flipped classroom |

Student at home watches a Khan Academy introduction to the French Revolution, and is asked to take notes on that presentation. |

Student comes in to class with notes prepared for a discussion. Students are asked to take additional notes as the discussion proceeds, and teacher collects notes at the end of class for evaluation. |

Adding Fractions

|

At school |

At home |

| Standard classroom |

Teacher presents the idea of adding fractions with different denominators, and does an example. |

Student goes home and does homework problems from his or her textbook. |

|

At home |

At school |

| Flipped classroom |

Student at home watches a YouTube video on adding fractions, and is asked to do attempt two different practice problems at home. |

Student comes in to class with practice problems completed (or not), and instructor gives an additional 15 problems of varying degrees of difficulty to reinforce the skill. |

You get the idea.

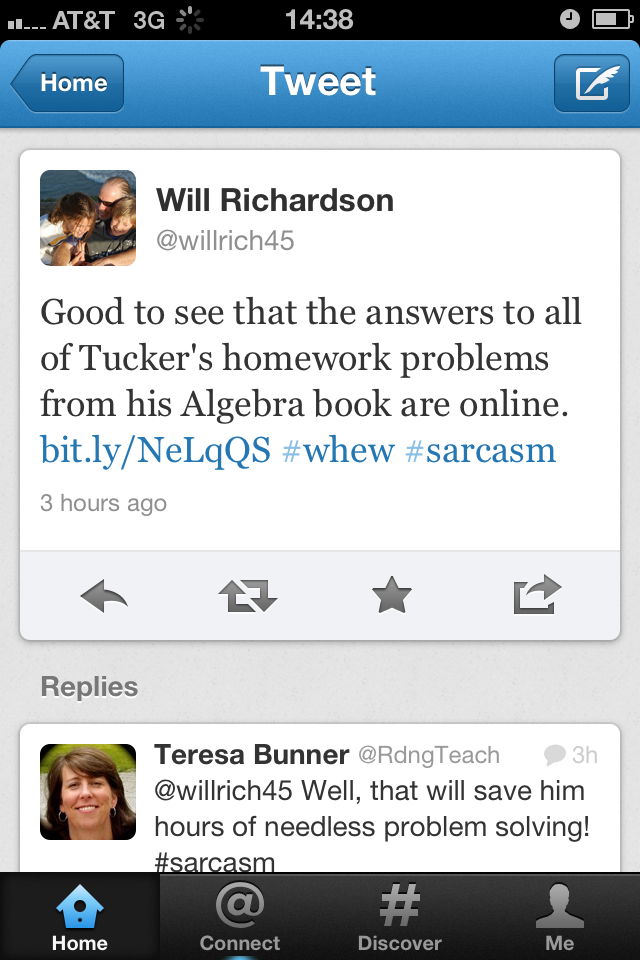

Think about assessment.

When students walk into class the next morning, how are you going to know whether or not the students have done their flipped-style homework from the night before? A warm-up activity? A quiz? A discussion in which each student is monitored for participation? My own students tend to try to get away with doing less rather than more, so you’ll need to identify a means for checking that they’re doing their new homework.

Allow for varying access to technology.

If students don’t have some sort of comparable access to technology, you’ll need to develop strategies for managing those differences. If a video lesson is being watched online, a teacher might send home a DVD that the student can watch at home. At-school access to the video, in the library perhaps, can be arranged for during other times of the school day. These factors can complicate your efforts to flip the classroom, but it’s important that all students be accommodated in one way or another.

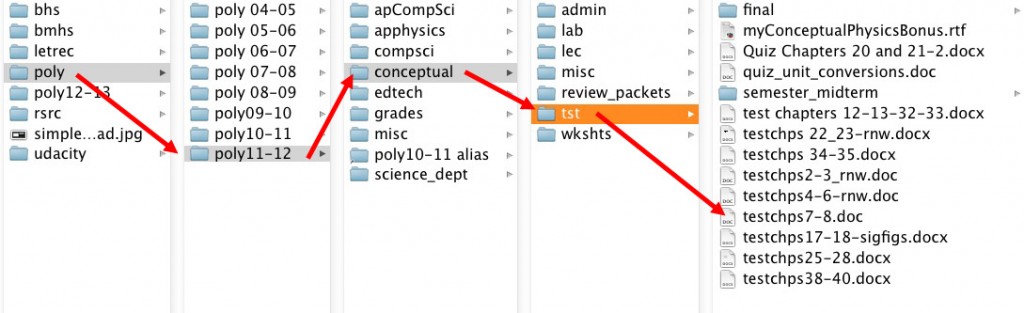

Create your own resources.

Ultimately, there will come a point at which you’ll find that what you need your students to see doesn’t yet exist, or maybe you’ll be inspired to develop something unique and personalized for them. Creating and uploading videos to YouTube is a relatively easy thing to do with the webcam that’s probably already included in your laptop computer. If you want a higher production value, or you want to capture your computer screen while showing a PowerPoint presentation, you’ll almost certainly have to buy some software that will allow you to experiment with that process. TechSmith’s Camtasia for both PC and Mac, and Telestream’s Screenflow for the Mac, are currently popular and powerful screen capture utilities. If you run Linux, you can do a $ sudo apt-get install xvidcap to install XVidCap, a live screen capture utility that’s very good, but lacks some of the high-end editing capabilities built into Camtasia and Screenflow.

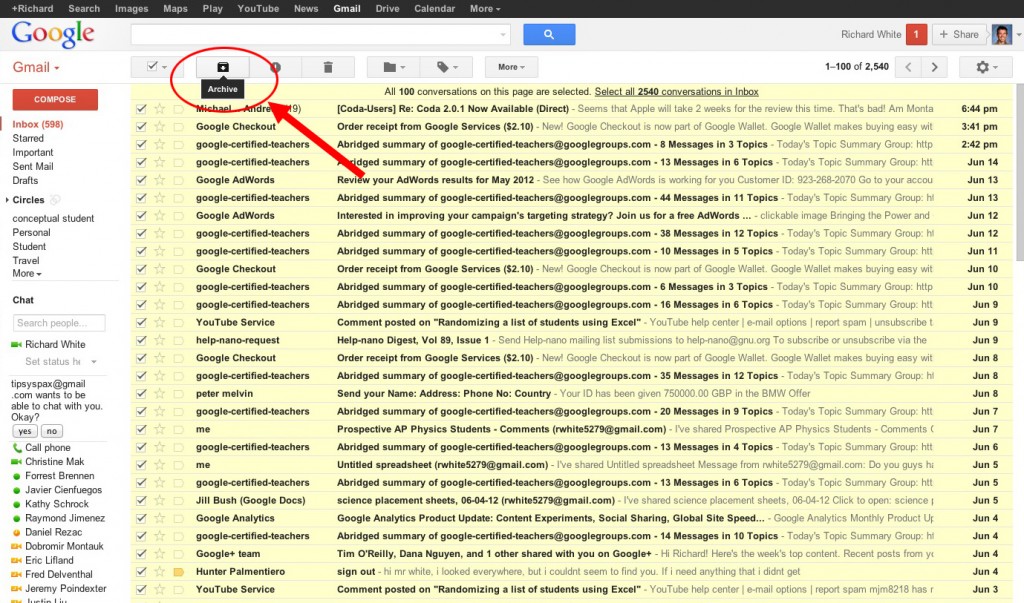

Make your materials available on a website.

Google’s YouTube is a powerful means of delivering videos, but it can be a distracting place to send a student for flipped homework assignments. At some point you’ll almost certainly want to create a webpage or website that will give students a one-stop shop for finding materials used in your course. Your school may offer the means of putting up a course webpage, but if not, you can certainly create your own. The quickest, easiest, and certainly cheapest way to do this is to use Google’s Sites feature, available with any Google account. Once you’ve got your page set up, you can use it to easily deliver flipped assignments to your students.

When you look at all of that up there, it seems like it’s a lot of work, but you certainly don’t have to jump into this all at once. Begin at the beginning, and move forward as your time and teaching assignment allow.

For more resources on Flipped Classrooms, see: