Whither Identity: Reclaiming your templated self

by Richard White

2014-10-05

Part III in the “Whither” series

Who owns your online data? Who owns the content that makes up the digital you? Is your digital identity locked into Facebook as a series of uploaded photos, status updates, and comments on others’ posts? Do you have a copy of your tweet timeline? If and when you decide to migrate from Facebook, will your digital identity travel with you?

Audrey Watters refers to the “templated self,” a digital “you” that is described and defined via the features and constraints of any given platform. As cyborganthropology points out, Facebook and Twitter are strongly templated, with structures are policies that are highly confining to interactions. WordPress and Google+ are less confining, but still require working within a templated (pre-structured) space. MySpace pages—to their own detriment—had much less in the way of structure (hence the obnoxious and hard-to-read backgrounds that some users delighted in presenting).

Creating one’s own website is the least restrictive platform of all, of course. User-created content is not shipped off to be stored in someone else’s silo, but is maintained and managed in one’s own domain.

How significant is this to you? Is your Digital Self hosted somewhere that’s “too big to fail?” “Software as a service” relies on a company maintaining support for that service. Some services/platforms that have gone away in the past year or two:

- Google’s social networking service Orkut

- Twitter’s image hosting service TwitPic

- Video streaming service Justin.tv

- Apple’s MobileMe shut down

- Yahoo!Blog shut down

- Everpix photo hosting service shut down

- Google Wave shut down

It’s no surprise that businesses and product lines occasionally fail or are discontinued, and that possibility is especially prevalent in technology, with boom-bust cycles akin to a bucking bronco. It’s all the more important, then, to give serious thought to how much of one’s identify one wants to invest in an organization’s template.

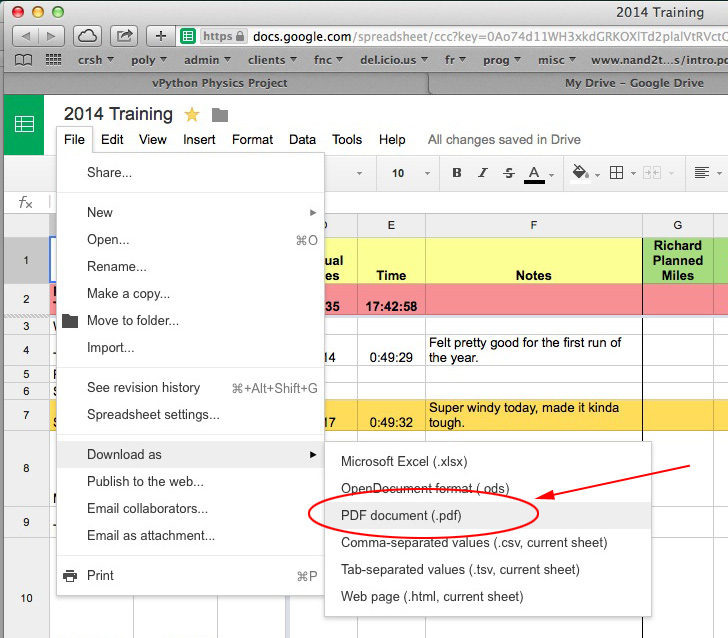

Closer to home—in our classrooms—it’s also the case that educational platforms enforce templated identities. Learning Management Systems, almost by necessity, structure content and data in such a way that it makes it difficult to move that data around to other places. Even something has simple and local as a classroom wiki doesn’t typically provide much in the way of data portability. The online grading program that I use for tracking my own students’ progress provides an Export utility that creates a CSV-based backup file for instructors, but provides no such option for students. Data that goes in to these systems very rarely finds its way out.

Another educational feature, perhaps peripherally related to the templated self, is the Digital Portfolio, which purports to provide some means of collecting, storing, and presenting a students’ electronic information over a longer period of time. I understand the desire for such a record–I have both digital and non-digital portfolios of work that I’ve done, assignments in school, artistic pieces, etc.–and I think schools are wise to be considering ways to implement these collections. (My school is in the process of discussing these possibilities right now.) I have to wonder, however, at the wisdom of paying for a storage/presentation service that places student assignments in a proprietary silo, with access controlled by a business that may or may not be around five years from now. Are there significant advantages here over the simple and expedient solution of having students place their most important work in a network folder?

The Internet began with a decentralization of access; anyone could access information from anywhere on the network. If Facebook and WordPress have given us templates, and in so doing forced a proprietary, siloed, centralization of our data, Watters encourages us to consider a “re-decentralization of the Web.”

If you’re interested in having an honest, long-term, presence on the Internet, reclaim your self. Get your own domain. Be who you are, rather than a Facebook status update that may or may not actually be seen by your friends, depending on whether Facebook decides to show it to them.

The original promise of the Internet was a democratization of voice: everyone had access, and everyone could be heard. Increasingly, however, voices are siloed behind paywall, registrations requirements, and licensing agreements.

Register your own domain, at hover.com or any one of hundreds of other registrars.

Reclaim your voice.

Reclaim your identity.