Part of the impetus for my writing lately is reflecting on what kind of changes have happened to my teaching as I move to Distance Teaching. In order to better understand that, I want to begin with a look at what my teaching looked like before, when I was teaching in a standard classroom.

Then we can talk about what I’m doing now and then do a diff on those two descriptions to see what’s changed.

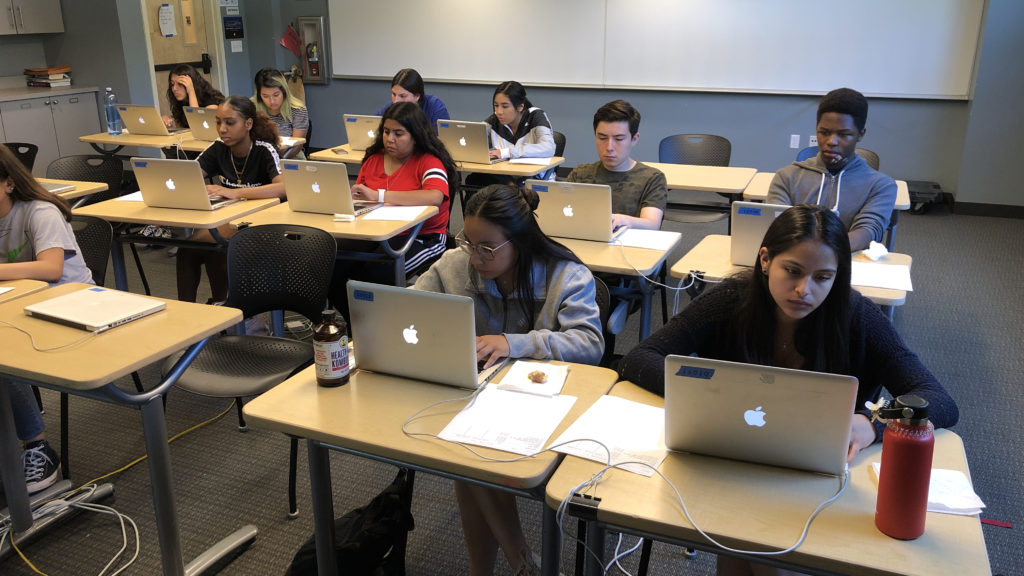

My school is a Bring Your Own Device school, so all students bring their own laptops to school every day, to be used in all of their classes. The majority of students use Apple laptops, with 1-3 students using Windows machines in any given class. My class sizes for the CS classes range from 8 (very small even for my school) to 18 (the upper end for most classes). Class is held in a standard classroom, with students seated in rows of desks facing the front of the room. I teach from a long demonstration table at the front of the room, with my laptop on one side, and my screen projected (via LCD projector) onto the whiteboard at the front of the room.

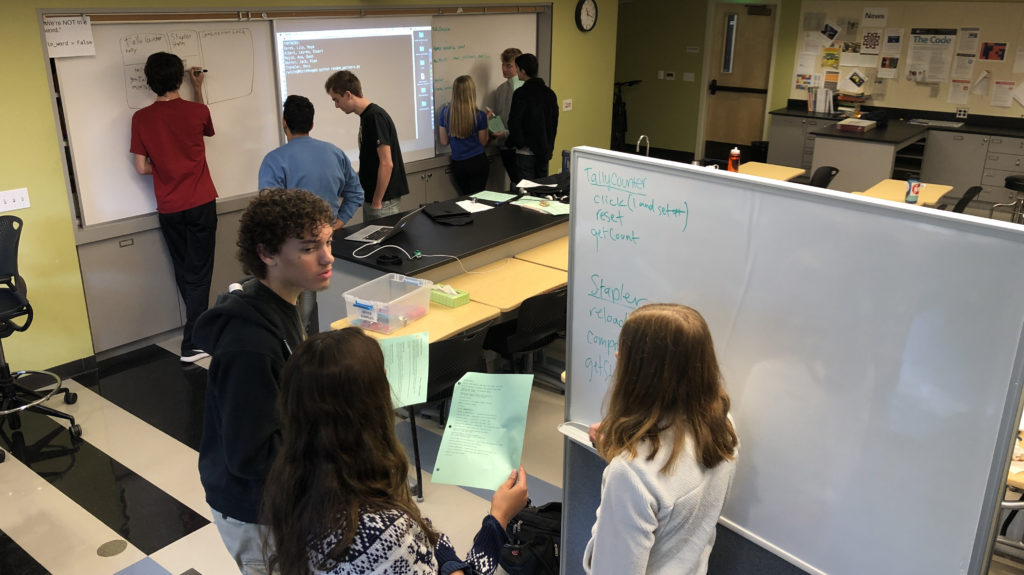

What we do in the classroom varies. Some days I’m introducing a new topic. That typically includes me projecting something from our course website–the description of a new data structure, say, and an example of that structure in use. I’ll annotate that projected information using a whiteboard marker, and perhaps develop new examples to either side of the projected image, interactively with students. Once the new topic has been introduced, students are directed to the assignment for the day/evening, also available on the website. I’ll typically give them a few moments to get started, and wander around the room checking in with them individually before returning up to the front of the room to begin my own development of a solution to the problem. Informal interactions and conversations inform our progress, and anything that isn’t finished in class is typically assigned as homework.

Upon completing an assignment, students upload the source code to our course server where I can collect it, run it, evaluate it, comment on it, assign points for completion, etc., depending on the assignment.

Other days I’ll spend more time developing a more complex idea, or spend a few moments describing our next project which might take a few days to complete. Some days are just work days, when students have the entire period to work on a project, on their own or with classmates.

Reflecting

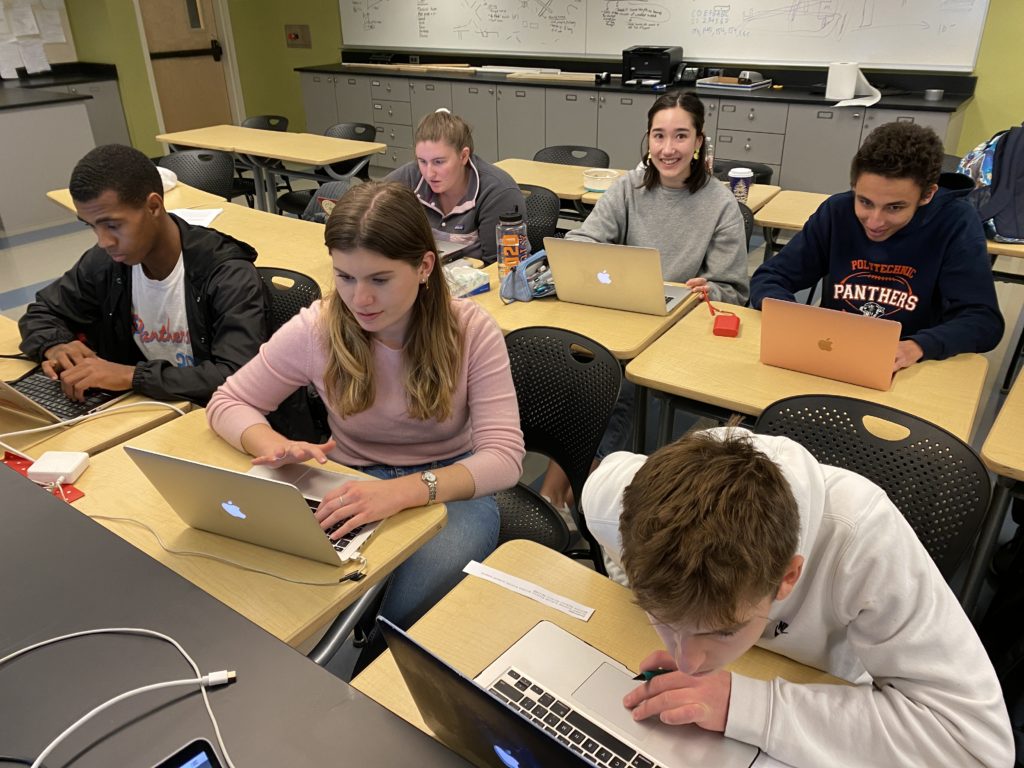

One of the things I’ve done well in my teaching, I think, is to bring students into the Computer Science tent who might otherwise not have thought to join us. This year, for the first time, we have 50-50 gender parity in the AP Computer Science classes, and although that number is not something that I’ve specifically targeted, I have deliberately made specific efforts to be more inclusive in my teaching and my outreach to prospective students. We should talk about that sometime.

I’ve worked to include things in my CS courses that are a little outside the standard curriculum, perhaps, in the interest of giving students a deeper experience. All students learn to use the Terminal, and all students submit assignments to the course server, giving them an experience beyond that of simply writing code in a browser interface. The Intro class, most years, includes a quick unit on websites, HTML/CSS, and responsive design. I know, I know, it’s not “real” computer science, but it gives them insight into an aspect of our technology-mediated world that they wouldn’t otherwise see.

And they’re so proud of the websites they create!

I’ve got a few areas that I could really stand to improve on. Although I love some of the larger projects I give my students, I don’t have a really big end-of-year project that could act as a sort of capstone for them. I’ve got a pretty good excuse: our seniors are done with school immediately after AP exams in early May, so I don’t have any “free time” with them at the end of it all. Still, that’s a goal of mine, to set up a nice project for them to really dig into at some point during the school year.

A big weakness of mine is giving CS students feedback on their work. I’ll give myself good marks for giving them scores, both for their daily assignments and their projects, but I haven’t yet figured out a good way to give them feedback in the midst of it all.

For some programs I’ll provide testers, and that’s a great automated way of giving them some specific formative feedback as they’re working on an assignment. For larger projects I’ll sometimes carve out an evening when I can sit down, run each student’s code, and provide specific comments on their work. Those remarks are often included in their actual source code as comments, which I’ll then either copy into their directories on the server (where they’ll probably never look at it) or print out and hand back to them in class (where they deride me for wasting paper).

So I guess I have two questions for you.

- How do you give feedback to students on their programs?

- What efforts do you make to ensure “academic integrity” in your CS program? Are students allowed to work together? How do you catch “cheating” when students are working on relatively simple coding assignments? Does it matter?

Okay, I guess that’s more than two questions. Sorry.