“Just In Time” Learning

by Richard White

2010-12-06

“‘Hybrid classroom?’ Seriously? What effect could Internet use possibly have on student learning in my classes?”

I’m SO glad you asked. I have data on that. I’m in the process of running an experiment.

I teach physics, a subject that has some reputation as being a little tricky to understand sometimes. Typically, teaching physics works something like this:

- I present material in class: discussions, lectures, demonstrations, sample problems.

- Students go home, try to do assigned homework problems, and get stuck.

- Students come back the next day with questions, and I spend time in class helping them clear up their misunderstandings.

It’s a time-honored process, and one that works on some levels. “Struggling with the material” is something that all learning requires, as each of us figure out how to fit new ideas into our previous understanding of the world. Constructing that new knowledge requires effort, and it’s absolutely part of my job to assist students in that process.

After 15 years of teaching physics, thoughI came to realize that there was a problem with the current homework system. Ater 15 years of teaching physics, I figured out that often, students were getting waylaid by relatively trivial difficulties, usually a problem-solving technique, or a strategy, or a “trick” that we’d discussed in class and that they hadn’t quite learned how to apply. It wasn’t that they had absolutely no idea of how to solve the problem—they just needed a little push, a little hint on what to do next, and the answers to the odd-numbered problems in the back of the book weren’t enough.

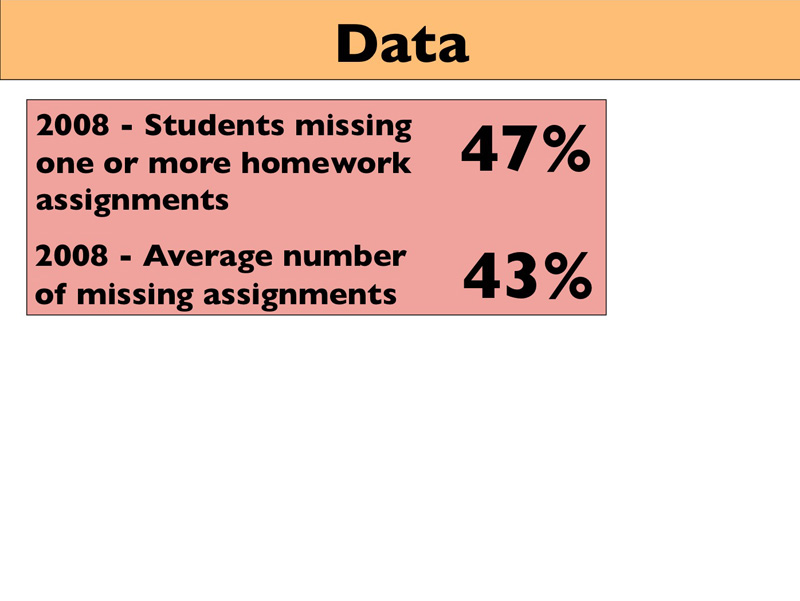

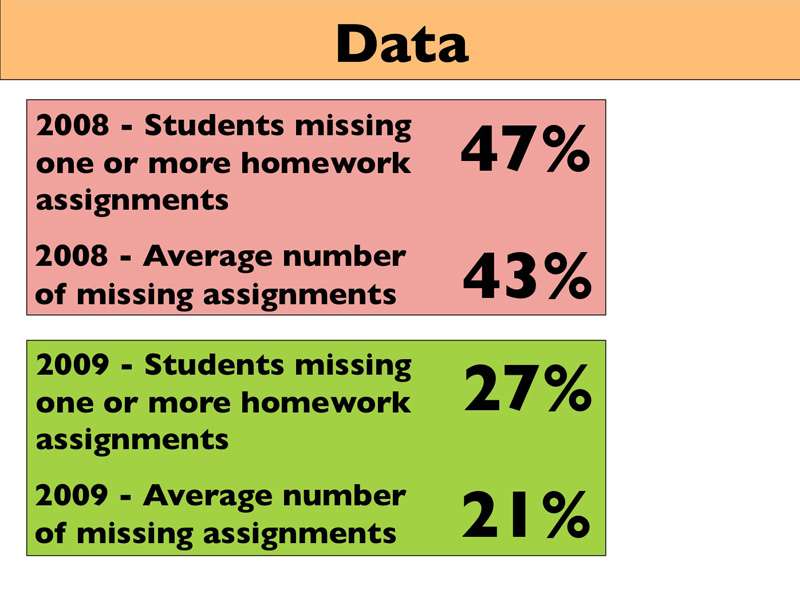

I had clear data that the students were getting stuck, based on the number of students missing at least one assignment, and—for those students—the number of homework assignments they were missing.

I made what I thought was a generous offer: the homework solutions were available in my office so that students could come in during office hours to take a look at them… but that didn’t really help them at night. At night was when they were working on the problems. At night was when they needed the help.

So I made the solutions available online.

It was a simple step, really, and I fully expected that a lot of the problems with “incomplete and missing homework assignments” would go away. I made sure to communicate the fact that these solutions were available for students to use in helping their progress after they’d attempted a problem; these were not to be copied. But there was that risk.

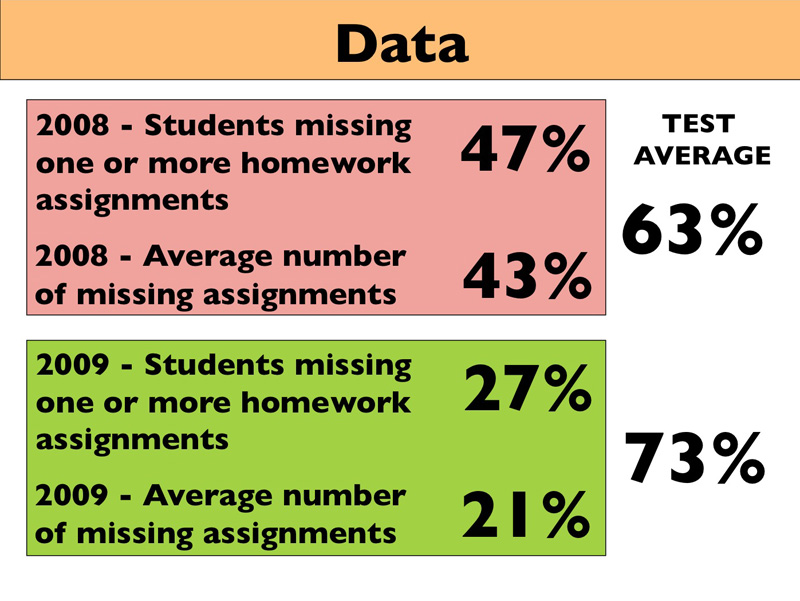

I’d hoped that the homework scores would improve, and improve they did:

That’s not much of a success story there, of course: “give students who haven’t been turning in homework the answers, and they’ll turn in more homework.” Great headline.

Here’s where things get interesting, though. Students both years took the unit test, with the following results:

Test scores went UP. Way up. On unassisted assessments of their learning, students demonstrated that their understanding of the material had improved by a whopping 10%, because (I believe) they were able to get some assistance with their homework when they were doing it, and not hours or days after the fact.

Of course, it’s well-known that the WWW is a great place for a motivated student to explore and learn. See the Wall Street Journal’s Turning Kids From India’s Slums Into Autodidacts for some interesting examples of this. Money quote:

Education, though, feels like one of those things that has to be top-down: There has to be a teacher and a taught. But plenty of people educate themselves. Is it possible for everybody to be an autodidact, now that knowledge is so accessible online?

The premise of the article is so radical that most classroom teachers may not feel that it has any bearing on what we do day-to-day. But my ongoing experiment has convinced me giving people access to new tools to guide their studies—even something as mundane as homework solutions— can have a powerful effect on the learning experience.

There are other things we can do as well. More about that next week.

First, a small quibble: can we just agree that “a little tricky to understand” is an understatement?

But apart from this, those are truly impressive data. This reminds me of my graduate school reading of Vygotsky, the old Soviet, who talked about “the proximal zone of learning.” This was a fancy way of saying that at any given moment, a student is at a particular spot with respect to his learning. He can get to the next level–the next thing to know, the next concept to master, the next operation to learn–if the optimal conditions are in place for that learning to occur.

Our system is set up in such a way that we pretty much offer one condition as the optimal one. I do an explanation, or maybe an demonstration in class, and then you go away (have lunch, play ping pong, attend a few more classes, go to sports), and try it at home.

What you propose here has some really interesting possibilities. I look forward to your next post!

What I love about this is how straightforward (perhaps that’s the wrong word) it is. I can remember when I first started teaching, and we were talking a lot about “teaching with technology” (which is, of course, a misnomer: pencils are technology too), and there was all of this concern about the need for a wholesale paradigm shift. I can remember teachers fretting that there is no value added to just adding computers to “what we have always done.”

Amid the push to better incorporate technology (computers) into our practice, many people simply did what they always did, but in a slightly more tech-savvy way. The teachers who simply took the same old handouts and emailed them– instead of photocopying them– were incorporating technology into the class, but what’s the value added then? Essentially, there is no change, except for saved paper and a higher risk of student distraction. The perception, at the time, was that if you weren’t radically rethinking the ways in which you incorporated technology into your class and presenting material in revolutionary new ways, you were doing it badly.

I’m not saying this is wrong– it might not be. But the concerns are pretty self-evident. Stubborn teachers resist change. Open minded teachers express interest in changing their practice think that they need extensive professional development to essentially re-learn how to be a teacher. Which costs tons, in time and money. All in all, the task seems too daunting, an uphill battle. Give me back my photocopies and leave me alone.

What you’ve done here– providing students with the answers in real time– is something different altogether. It’s not exactly radical, but it’s innovative. What strikes me is that it doesn’t require a complete paradigm shift or require us to rethink our roles as teachers. In fact, it was the proficiency and self awareness with which you were doing it the old way (struggle through the homework, go over it in class… just like when we were students) that tipped you off to a new idea: give them the answers when they need them most– when they are struggling through the problems. The technology was incidental– merely a tool you could use to do what you always do in a different/better time-frame.

In my mind, this does exactly what technology in the classroom should do– not rewrite what it means to be a teacher, but allow us to address the age-old challenges of teaching and learning in new and innovative ways. Keep the ideas coming.

First, a small rebuttal, no, can’t agree with you Jamie.

My quibble, Richard, is regarding the “2008 – Average number of missing assignments” statistic. What did you average and how did it equal 43%? Did you find the mean of something?

I started doing the same thing this year in my 9th grade GAT math course. I post my worked out solutions on my web page. Since this is the first year I have taught GAT, I have no basis for comparison, so I will not know if posting solutions is having the same impact in my class. My concern is that many students are not utilizing this resource. I have made it compulsory on a few occasions for them to correct their work with the answers.

Just so I understand: you post solutions before the assignment is due, correct? So, if I am in your course, I could be sitting at my desk doing my physics homework, and, should I get stuck on #6, I could navigate to your site and see your solution to #6 and use that to correct my thinking? Is that your expectation for how it gets used?

Thanks for the comments, Cotter–you’ve really focused in on exactly how I feel about technology and teaching. There are going to be some revolutions along the way, perhaps, but most of what I’m going to be doing in my classes on the local level, day-to-day, are typically small tweaks with some “bang for the buck”; something significant, but do-able by me, given various constraints (mostly having to do with mundane realities like having to eat, sleep, and breathe every so often).

Josh, the graphic was taking from a PowerPoint presentation during which more information regarding that statistic was given. The 47% refers to the percentage of students in my AP Physics class that had not turned in at least one assignment during the time period in question (the unit lasted about 3 weeks). The 43% refers to the fact that, for those students who were missing at least one assignment, the average number of assignments they were missing from my gradebook was 6 out of 14 collected. Some were only missing 2, some were missing 10, but the average number of missing assignments of the 14 I’d collected was 6.

I have the advantage in AP Physics that most of these students are highly motivated to do well, for lots of different reasons, so they mostly do make good use of the resource. We spend time in class talking about how it’s not really going to help you very much if you just copy the solutions down… and in fact, some of them are quickly coming to learn how true that is this week. In any event, I think that the potential misuse by a few students is far outweighed by the advantages that the resource has provided.