It’s All About the Process

2011-11-29

by Richard White

Back in the day, “Project-Based Learning” was one small but powerful attempt at reforming some of what was wrong with some of our K-12 educational thinking. The general idea was that larger term projects—hopefully projects with some relevance in the Real World—were a better context for student learning, as opposed to a series of smaller and often disconnected-seeming homework assignments or worksheets.

We also had “Authentic Assessment,” in which the tasks students were asked to perform and be assessed on were “either replicas of or analogous to the kinds of problems faced by adult citizens and consumers or professionals in the field.” (Wiggins, G. P. 1993. Assessing student performance. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.) The typical product of an authentic assessment-based assignment would be a product that students could market at the school or community level, or a presentation to a gathering of community leaders regarding some local issue.

I’m actually a big fan of both movements, but I think it’s important to keep in mind that for our students, now more than ever, the end product is less relevant than the process by which one arrives there.

It’s a concept that bears repeating. For K-12 instruction, process is everything. The final product is less important.

Here’s why.

You’ve no doubt heard how quickly things are changing in our Western Hemisphere, technology-driven, North American world. One of the devices that I use most frequently during the course of the day, my iPhone, didn’t even exist five years ago. The web browser I use, Google’s Chrome, is one of Google’s famously beta releases that was released for the Mac less than two years ago. If your students are using technology in any way as part of their work in your class—and they absolutely should be!—then you need to be teaching them knowing that the technology is going to change.

This philosophy extends even to non-technology situations. In the AP Physics course I teach, it’s common knowledge that I don’t care much about the right answers. Hell, I’ve given them all the right answers by making the solutions available to them. What I’m interested in is the answer to this question: “Do you know how to ‘think’ physics?” Have you acquired the processing skills that will allow you to analyze a situation, develop a problem-solving approach, and execute that approach in order to arrive at an answer?

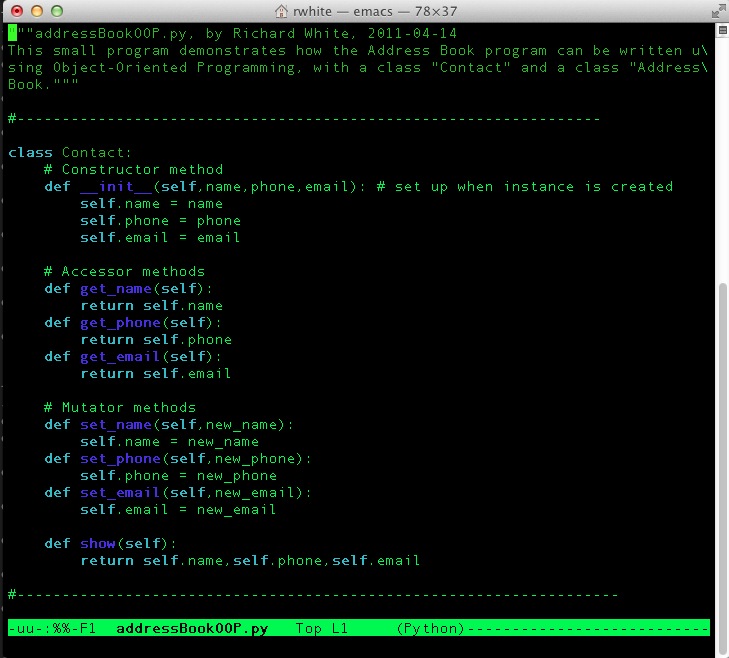

In the computer programming class I teach, when I given them an assignment to code a database-driven Address Book program, I don’t have any great need for one of those programs—there are dozens of commercially-available ones, most of them better written than something that my students will be able to come up with. But it’s the process of thinking about User Interaction, efficient coding, validating input, sanitizing input, designing and interacting with a database, that they will go on to use at some point in the future. In the meantime, the Address Book project is simply a context that allows them to explore those topics.

Do I want an Address Book program? No. Do I want them to know how to write an Address Book program? Absolutely.

It occasionally happens that a student of mine—typically a very bright and perceptive student, what teachers sometimes refer to as a “quick study”—will complain about the fact that I’ve docked them points for missing homework assignments, even though they’ve scored exceedingly well on the exam for that topic. “Come on, Mr. White. I obviously know this stuff!” This typically happens during the first semester when the topics of study—Newton’s Laws, conservation of energy—are ideas that are already familiar to them, or at least somewhat intuitive.

Second semester it’s a different story, when concepts like “charge density” and “magnetic flux” aren’t quite so easy to grasp. Students who have developed a system for working through the material are able to apply that system to the new material, while the “bright” student, for the first time finding that the material isn’t coming as easily as he’d thought it might, flounders about and wonders what went wrong.

It’s in our students interest to learn processes, ways of thinking, and ways of learning. Facts are important, of course—it’s a serious impediment to one’s study of chemistry if can’t immediately recall that the sulfate ion is SO42-—but it’s also important to know how to evaluate an oxidation-reduction reaction. That’s a process that can be used to analyze a whole series of different reactions.

Most of the teachers I know do this almost as a matter of instinct now, but it never hurts to go back and reflect on what we’re doing, especially for assignments that we’ve developed and been giving to students for years. In our Conceptual Physics class this year, we’ve eliminated the discussion on photo-sharing on Flickr—students do their own photo-sharing on Facebook and other sites all the time now, and don’t need formal instruction in that area any more—in favor of expanding our instruction on using Excel to process and analyze the data from their experiments.

Is Excel important? Somewhat. Is knowing how to create and manipulate a spreadsheet? Absolutely!

The Process. It’s everything.